In an age where film discourse is reduced to “good” or “bad,” I find such binaries reductive—especially with a film like Superman. This isn’t a review; it’s a reading. A cinematic work like this doesn’t ask for judgment—it demands reflection. So rather than rating the film, I want to consider what it’s doing, what it’s responding to, and why it feels so urgently of this moment.

Returning to a Myth with an Updated Mirror

Superman doesn’t reframe its mythology as much as it reactivates it. The original comics, born during the Great Depression, were a response to authoritarianism, social inequality, and economic collapse. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—both sons of Jewish immigrants—imagined Superman as a working-class hero, not a deity. He fought corrupt landlords and abusive employers, not aliens or gods.

Today’s Superman feels like a reawakening of that origin myth. While the exact sociopolitical circumstances have shifted, the undercurrents—fear, control, inequity, authoritarian drift—remain startlingly familiar. Like its 1930s predecessor, this film uses fantasy to interrogate the world, not escape it.

Power, Surveillance, and the Visibility Trap

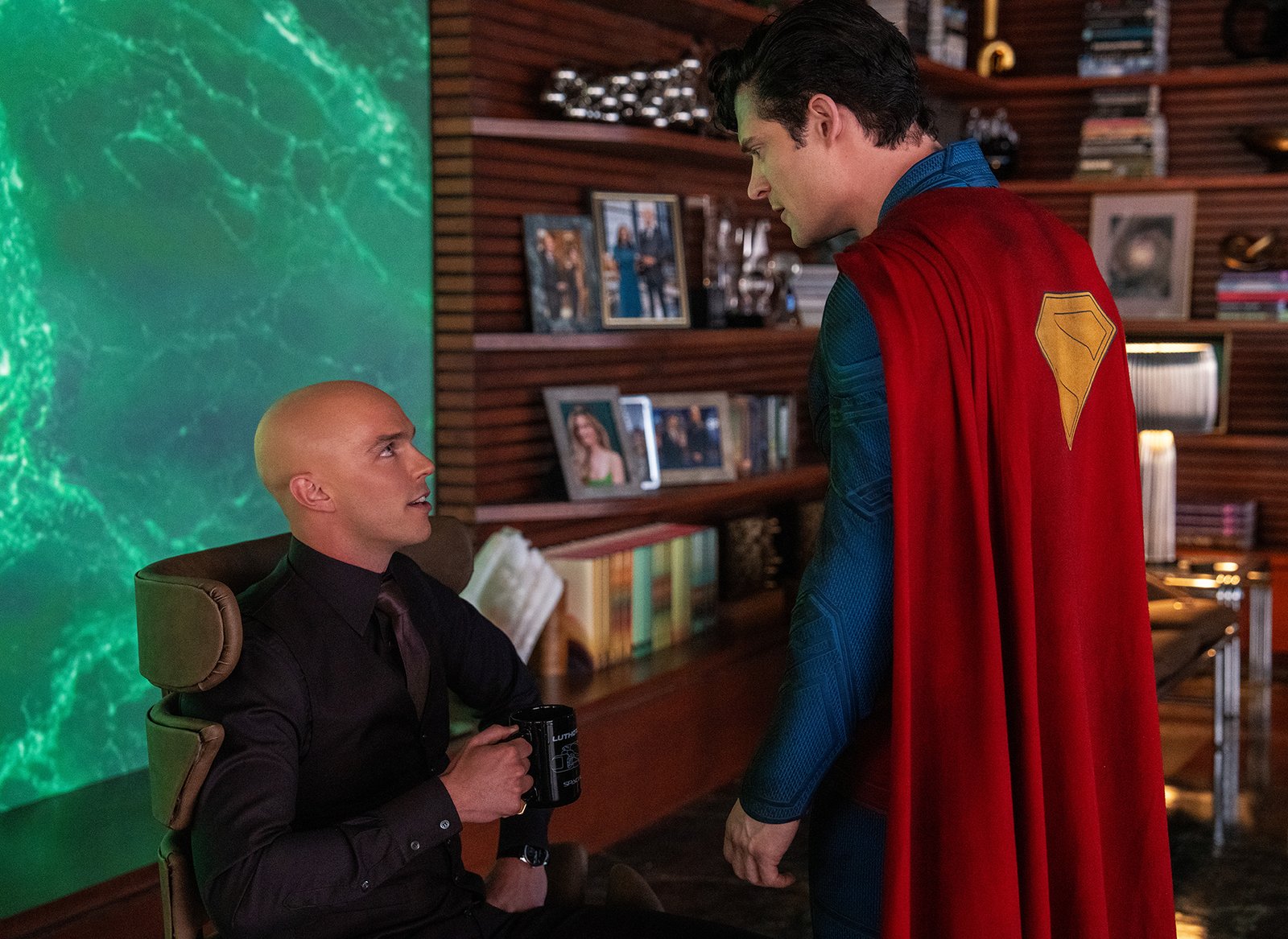

The film’s philosophical core rests on the ethics of power. Sure, we get the expected good-versus-evil showdown, but the real question lurking beneath the cape and tights is more unsettling: what is power, how does it behave, and what intentions lie beneath its surface? In this world, morality gets dictated by how might is wielded, not by might itself.

The film leans into a notion of universalisation—a moral framework that transcends borders, species, or origins. Superman’s strength comes from his capacity to care without controlling, which, let’s be honest, is a fairly radical concept in our current political moment.

The antagonist represents something far more insidious than your garden-variety supervillain: the danger of benevolent control. A regime cloaked in progress, optics, and media spin. Here’s where Michel Foucault’s theory of the panopticon becomes relevant—the idea of being watched not to be punished, but to be conditioned. In this film, surveillance has become ordinary. Superman is monitored, judged, and scrutinized constantly. The gaze isn’t a villain; it’s systemic.

Foucault wrote, “Visibility is a trap.” And in Superman, the trap is ever-present. The hero finds himself trapped in the expectation of moral perfection, held to impossible standards not by a villain, but by society itself. This creates a fascinating tension: the very transparency that makes him trustworthy also makes him vulnerable to manipulation and control. It’s enough to make you wonder if the real kryptonite isn’t green rocks, but public opinion.

The Radical Act of Accessibility

At moments, Superman feels too earnest—too neat. The messaging is unmissable. The speeches are stirring. The villains, polished but insidious. At first, it feels almost corny. Too obvious.

But what if that clarity is intentional?

What feels simplistic to the educated viewer may be strategically accessible to the everyday one. And that, in itself, is radical. The film speaks plainly because, perhaps, it needs to. In a media landscape where everyone’s talking past each other, there’s something refreshingly subversive about just saying what you mean.

Like the wartime cinema of the 1940s, the film’s messaging feels deliberately shaped to cut across class divides and educational barriers. Casablanca spoke to moral courage wrapped in romantic sacrifice. Mrs. Miniver was so moving in its portrayal of everyday resistance that Churchill said it was “worth a hundred battleships.” And The Great Dictator, Chaplin’s first talking role, abandoned subtlety to deliver one of the most direct anti-fascist monologues in cinema history.

These films weren’t subtle because subtlety wouldn’t have worked. The world needed clarity. So does ours.

Superman becomes part of that lineage: a populist parable delivered in emotionally readable terms. A myth for everyone, not just the cultural elite. It speaks to the working class, the disaffected, the politically fatigued—reminding them that they are still seen, still part of the moral conversation. Which is a hell of a thing to attempt in a superhero movie.

Visual Language and Symbolic Resonance

The film’s power lies not just in its dialogue but in its imagery, which operates on multiple levels of meaning. The Arctic tableau of a bloodied Superman calling for Krypto operates as both superhero spectacle and metaphor for how our ideals look when subjected to real-world pressures. Superman, stripped of his invulnerability, becomes a mirror for our own fractured public consciousness. The scene works because it shows us vulnerability without shame—a rare thing in our performatively tough culture.

Media manipulation threads throughout the film with surgical precision. The antagonist’s mastery of optics—PR briefings, photo ops, orchestrated interviews—feels ripped from contemporary politics. Behind the scenes, we see the machinery of control: surveillance footage, drone monitoring, the constant threat of deep-fake manipulation. The message becomes clear: physical strength matters less than narrative control. The ability to shape story trumps the ability to bend steel, which is either deeply cynical or deeply true, depending on your mood.

Krypto the Superdog, often played for laughs in other contexts, becomes something deeper here—a totem of compassion and authenticity. He grounds Superman emotionally while representing innocence untouched by surveillance or propaganda. In a film where every action is scrutinised and every motive questioned, Krypto’s simple, uncomplicated loyalty serves as a reminder of what Superman aspires to be: good without calculation, protective without agenda. It’s almost enough to make you believe in pure motives again.

In Defense of Simplicity: Who Is This Film Really For?

Among the reviews circulating, some have branded Superman as “mediocre” or “corny.” Critics have lamented its lack of cerebral depth, its moral clarity, or its refusal to engage in the darker, moodier tone popularized by contemporary superhero cinema. But I’d argue that this criticism misses the point—and reveals more about the critics than the film.

The film’s intelligence isn’t cloaked in ambiguity or dressed in irony. Its power lies in its clarity, in its decision to be understood by all, not just by the self-anointed cultural elite. Professional critics, online theorists, and cinephiles craving complexity are reading the film through a lens that assumes all valuable art must be layered, opaque, difficult. But James Gunn, whether consciously or not, has crafted something more radical: a film that speaks in accessible terms to a wide audience, without dumbing itself down.

This film wasn’t made for the critics. It wasn’t made to impress the Criterion crowd. It was made for the masses—for everyday people, for those who don’t live in the bubble of cultural discourse. Its dialogue is straightforward because its message is urgent. And its simplicity is a design choice, not a flaw. (Though try explaining that to someone who thinks accessibility equals mediocrity.)

Superman comics have always done this. Their narratives were clear enough that a child could understand the message: do good. Protect the vulnerable. Resist tyranny. That same message is alive here, still vital, still unpretentious. Still for everyone. Because ultimately, whether you have advanced degrees or work with your hands, whether you’re a cynic or a dreamer, Superman is readable. And that’s not mediocrity.

That’s myth, made for the people.

A Mirror, Not a Monument

In the end, Superman asks difficult questions in ways that feel accessible—because that’s how change begins. It reminds us that the fight for justice isn’t always cinematic. Sometimes it’s bureaucratic, invisible, exhausting. And that the real villains don’t laugh maniacally—they smile through press releases. (A depressing thought, but probably accurate.)

This film isn’t perfect. It isn’t meant to be. It’s a mirror, not a monument. A reflection of how our systems shape our stories, and how those stories, in turn, shape our systems. By refusing to intellectualise itself into obscurity, it dares to speak to everyone. And that, in a media landscape increasingly designed to divide, might just be its most heroic act of all.

The film succeeds because it remembers something we’ve forgotten: sometimes the most sophisticated thing you can do is be simple. Sometimes the most intellectual approach is to trust your audience’s intelligence without insulting it. And sometimes, in a world drowning in irony and cynicism, the most radical act is to believe in something good.

Now that’s a myth worth making.